The History of Mokume Gane | Part ONE

Development of Mokume in Japan

Mokume Gane Vessel by Gyokumei Shindo. Copper and kuromido.

“Work always from the heart. Love the hammer, let every blow gently knead the metal … listen to the metal and do not make it cry. Love the metal, and it will love you back.”

Tsuba by Denbei Shoami. Copper and Shakudo. Photo: Pijanowski.

An Ancient metal art re-discovered

There are actually two histories to the development of mokume gane. The first has its beginnings in Feudal Japan, obscured by time and the secretive nature by which knowledge of this kind has passed from master to apprentice through the centuries. The other is the history of mokume gane in the West, beginning with the technique’s “discovery” in the late 19th century, to extensive research and development that was carried out the 1970s and 80s. Two people stand out clearly as essential contributors to our understanding of both of these periods in history. They are Hiroko Sato Pijanowski and Eugene Michael Pijanowski. I will draw heavily upon their research in this chapter and believe without their important work that mokume might still be to us in the West an obscure and little-understood curiosity from ancient Japan.

MOKUME in Japan

In 1970 the Pijanowskis attended an exhibition of traditional Japanese craft at a Tokyo department store. It was there that they saw Gyokumei Shindo’s large raised mokume vessel shown in the above photo. It was a revelation to them, beautifully wrought and “having a surface effect of polished marble.” Up until that time, their own working knowledge of the technique was limited to solder-bonded laminates only. Their experience with this had taught them that raised pieces like Shindo’s were impossible to form with soldered mokume due to the fragility of the solder bond. They were drawn to discover how this vessel had been created and succeeded in befriending Shindo and two contemporaries, Masahisa Yagihara and Norio Tamagawa. From Shindo they learned the origins of diffusion-welded mokume. The Pijanowskis wrote:

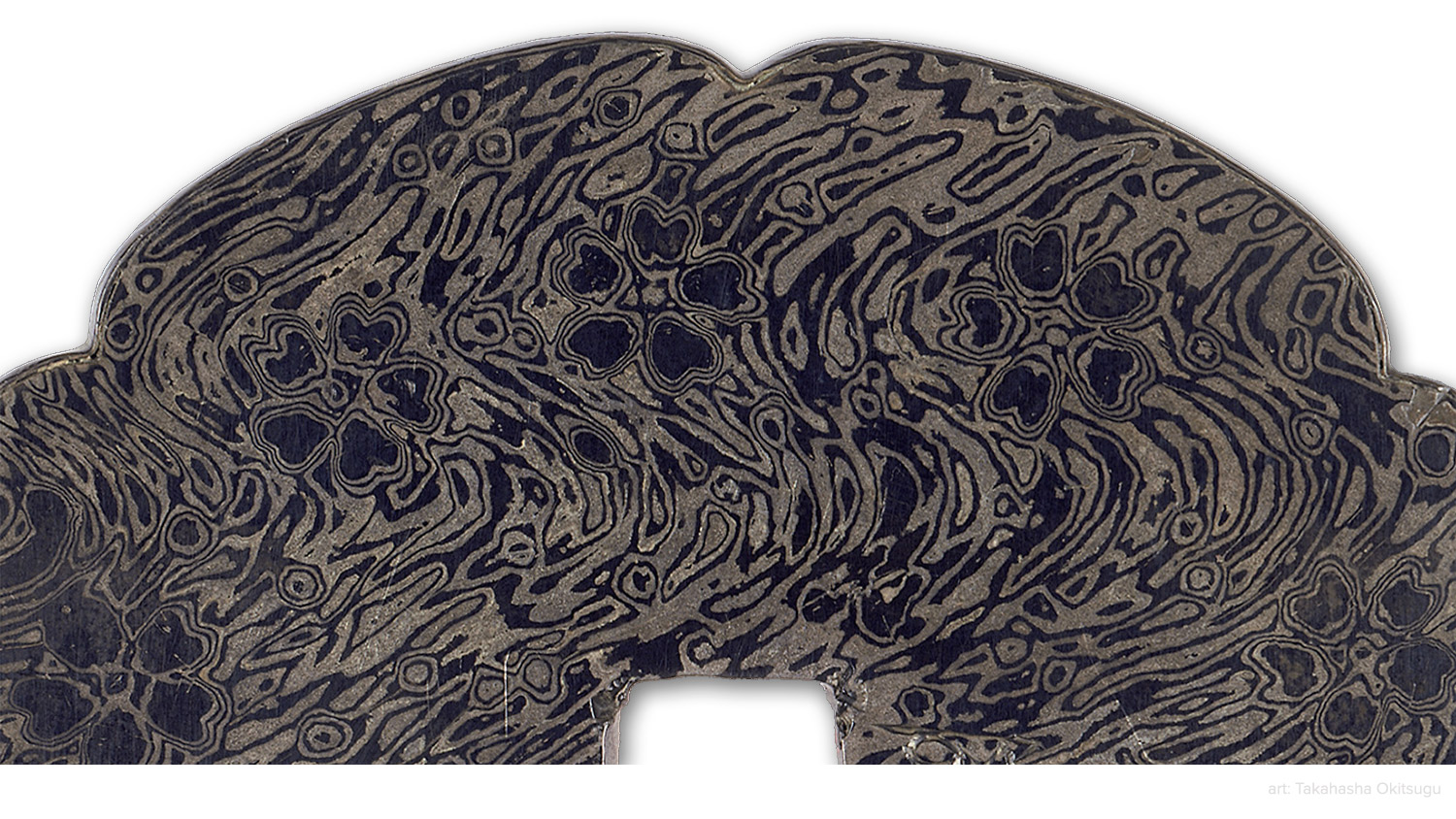

Tsuba by Takahasha Okitsugu. 19th Century. Probably Shibuichi and Shakudo. Pattern depicts plum blossoms floating on water. Courtesy: Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. William Sturgis Bigelow Collection.

“Mokume Gane was invented by Denbei Shoami (1651-1728) who lived and worked most of his life in Akita Prefecture in northwest Japan. He was a superb craftsman, and was given permission to use the name Shoami from the Shoam School, which began in Kyoto in the late 1500s. He was supported by Satake, the feudal lord in the Akita area at that time. Shoami first called his new technique Guri Bori because the pattern on his first non-ferrous mokume gane tsuba was like guri, a Tsuishu technique in lacquer work originating in ancient China. Tsuishu is one of the techniques where patterns are achieved by carving into thick layers of different colored lacquer; when line patterns are created, it is referred to as guri. He later named this technique mokume (wood grain) gane (metal). Shoami’s oldest work with these patterns was in the kozuka (sword hilt), where he used gold silver, shakudo and copper laminates. Shoami was clearly influenced by sword making, where he first found that non-ferrous laminates could be joined together to create patterns similar to lacquer work and pattern-welded steel. He adapted the principles of forge-welding to create mokume gane. Though Shoami is known as the inventor of mokume gane, this was only one facet of his work. He was also a historically important craftsman who produced excellent examples in steel of sword furniture and sword fittings with carving and inlay.

“In addition to advance sword-making techniques used in Japan at that time, several other factors led to the development of mokume gane. Among them, the high level of skill, extensive knowledge of metallurgy, and the ready availability of materials and the colored alloys already in use by Japanese craftsmen. These factors plus the accumulated knowledge that had passed from master to apprentice for generations all contributed to make the invention of mokume gane possible.”

Container by Hirotoshi Itoh. Copper, shakudo and gold. Photo: Meeten.

In fact, the art of sword-making in Japan at that time was so accomplished that it directly influenced all forms of metalwork. The importance placed on swords in feudal Japan and the influence of sword-makers on Japanese art and technology is not unlike the leading role the aerospace industry has in driving the technological advances of today. Swords were considered highly utilitarian and highly decorative at once. The finest artists and metalworkers of the day worked side by side to create swords of great beauty and remarkable functionality. Perhaps, one day, our own culture will ascend to the same heights by combining the efforts of NASA and the NEA!

Few examples of early mokume gane work are to be found today. What mokume work does exist from that period is confined to sword furniture. No doubt the technique was passed down from master to apprentice throughout the centuries in the fashion of traditional Japanese artisans. At some point in time, exactly when remains unclear, Japanese craftsmen began using mokume gane for other decorative objects. In an 1893 paper for the Journal of The Society of Arts, Professor W. Chandler Roberts-Austen describes a pair of mokume vases from the Kensington collection:

Box by Hirotoshi Itoh. Copper and silver. Photo: Meeten.

“… it is of great merit as regards the manipulative skill displayed in its production. The neck, band and foot are of shakudo inlaid with gold, while the body of the vase is of mokume consisting of alternate layers of shakudo and red copper, and there is a silver panel bearing a bird beautifully wrought in gold and colored alloys beaten into the silver.”

We can reasonably presume that if a vase of this complexity had found its way into the British royal family’s collection at the end of the 19th century, that similar work must have been produced in Japan for some time. Again the Pijanowskis relate:

“While the technique was passed down through the centuries, it remained relatively obscure until surfacing in the work of Soko Hirata, a professor in the silversmithing department of the Tokyo University of Fine Arts in the early 1900s.”

Another Japanese master by the name of Hirotoshi Itoh taught the technique of mokume gane at the University until his death in 1998. Itoh's teachings and philosophy profoundly influenced the work and lives of his students. The method of mokume gane continues to be taught at the Tokyo University of Fine Arts and Music.

Currently, the most accomplished practitioner of mokume gane in Japan is Mr. Norio Tamagawa. He is a ninth-generation metalsmith and was a student of Gyokumei Shindo. He practices traditional techniques, which are described below by the Pijanowskis:

Raised Vessel by Norio Tamagawa. Copper, silver, and shakudo. Photo: Pijanowski.

Raised Vessel by Norio Tamagawa. Copper and Kuromido. Photo: Pijanowski.

Norio Tamagawa at work. Photo: Meeten.

Diffusion by the Traditional Method

“Some of the metals Tamagawa uses for possible two and three metal combinations are copper, shakudo, kuromido, and fine silver. He usually uses eight layers of either round or square metal plates about 4 mm in thickness and 9 cm in diameter. Other Japanese artisans use between 1mm and 4 mm thick square sheet with the number of layers ranging from eight to twenty layers. The important thing is that the layers should be of the same thickness. Layers are annealed and completely flat, and all surface marks are removed with an abrasive paper or cloth.

“A rusted steel tray is used to contain the layers of the mokume billet as illustrated below. The steel tray has a window or opening on at least one side so that heat-generated colors and sweating can be observed while firing.

“Mr. Tamagawa uses a thick slug of copper approximately 1/3 the total thickness of the layers as a back up that will become the inside of his raised forms. He also uses a piece of mild steel the same dimensions as the copper backup slug; this acts as a weight, and is also rusted. The metal is chemically cleaned in a solution of 5 grams of potassium cyanide in 1 quart of water. It is then rinsed in clean water and dried with a lint-free cloth. The metal is stacked in one of the possible combinations listed below:

Copper, shakudo, copper, shakudo, copper.

Copper, fine silver, shakudo, fine silver, copper, fine silver, shakudo, fine silver.

Copper, kuromido, copper kuromido.

Copper, fine silver, kuromido, fine silver, copper, fine silver, kuromido, fine silver.

“The lower melting temperature metals are placed between the higher, in the sequence desired and put into the mild steel tray. Next the plate of mild steel is placed on top as a weight. Using thick iron wire, Tamagawa binds the layers tightly together.

“The tray containing the laminates is put into a hot forge that is fueled by metallurgical coke (a very refined and clean burning coal product). To this has been added hardwood charcoal, which produces a reducing atmosphere. The box of stacked metals is then heated carefully to the point where the edges start to sweat. Upon sweating it is immediately removed from the forge and lightly tapped with a wooden hammer. If the layers appear to be properly bonded, the binding wire is quickly removed and the billet is hot forged. If the stack contains silver, forging must wait until the mass loses its red color. The billet is further reduced by alternately forging and annealing to about 5 to 7 mm.

“Mr. Tamagawa patterns his mokume using a traditional tool known as a hatsuri-tagane, which is a cutting chisel shaped like a wood gouge that produces U-shaped channels in the metal. (See: “How To Make a Bullnose Chisel” in Chapter 7: Firing Methods). The laminated billet is held in either a pitch block, or large machinist’s vise. He then carves through at least three layers of the billet using the hatsuri-tagane to create the desired pattern. After removing the billet from the holding device, he forges it until it is completely flat.

“This sequence of carving and forging is repeated at least four times, all the while observing and refining the pattern as it emerges. After the pattern is set and the gouge cuts are flush with the surface, he continues forging until the desired sheet thickness is achieved. The patterned mokume gane is now ready to be raised or formed by conventional methods. After the mokume gane is formed and the final finish given to the metal surface, a coloring process using a unique Japanese patina called rokusho is used to bring out the colors of the metal.” (Please see Chapter 10: Finishing Techniques for more information on rokusho.)”

New Layers — What We’ve Learned SInce

Tiffany Mokume Vase in Gold, Silver, Copper and what looks like Shakudo. From the collection of the Cooper Hewitt Museum.

Tiffany Mokume?

One of the biggest omissions I made when first writing about the history of Mokume Gane in the book was excluding Tiffany & Co. from the story. I had heard rumors of their Mokume work, but a few years after publishing this book, I received and email from a gentleman with a picture attached of a large urn made of Mokume bearing the Tiffany hallmark. It was dented and oxidized from years standing unattended in the corner by the front door as a resting place for the family’s umbrellas and walking sticks. Apparently a visitor with some knowledge of Mokume had chanced to see it and informed the family of their treasure. They then had searched online for information on Mokume and found me. From their pictures I was able to affirm that it did indeed appear to be authentic and encouraged them to contact Tiffany’s directly. Sadly, I never heard more from them, but the piece was similar to the one shown here.

This is a stunning example of the very best of Tiffany’s Mokume work that was created for the 1889 Universal Exposition in Paris. Edward Moore, Tiffany’s artistic director, was responsible for this and the other Mokume works that they produced in the late 1800s. When Japan had re-opened trade with the West the the last half of that century, many objects of art were produced for export including some containing Mokume Gane. These apparently became a fascination to Moore who was determined to have their studio produce similar work. Moore had no way of knowing that the layers of Japanese Mokume Gane were bonded together without the use of solder, and very naturally assumed that they were. To my knowledge, all of Tiffany’s mokume was solder-laminated and the telltale pits and delaminations of this method are readily apparent when examined closely. That being said, the work that they created with Western methods was quite astounding and their promotion of the technique surely played an important role in planting seeds in the minds of Western metal workers that grew and blossomed in the US nearly a century later.

Detail of Tiffany Mokume Gane Match Safe.

From the Book’s Gallery

©2000-2019 STEVEN JACOB INC. All rights reserved. Copyrighted materials – no portion to be reproduced without written permission from STEVEN JACOB INC.